Hello everyone, this is Laurent Breillat for Learn Photographyand welcome to this new video!

I’m writing and recording this video when we’ve been confined for almost 2 weeks to limit the spread of the coronavirus. By the time you see this video, we’ll probably be confined for a month or so. I hope that you and your loved ones are doing well, and if you are one of all those who contribute to keeping the society going, a big THANK YOU. 🙂

I am very lucky, because confinement affects me very little in my daily life: I already work 100% from a computer, and the whole team at Learn Photo is already teleworking. Anyway, anyway, the transition was as easy for me as not opening my front door..

That said, even if practically speaking it’s simple, I’m not without a certain amount of anxiety. Returns are a bit ubuesque, with the disinfectant wipes to clean the packaging, it’s still a bit surreal. It’s not irrational at all, since in reality it could be a vector of contamination, but it reflects a rather particular fear: that of the invisible threat.

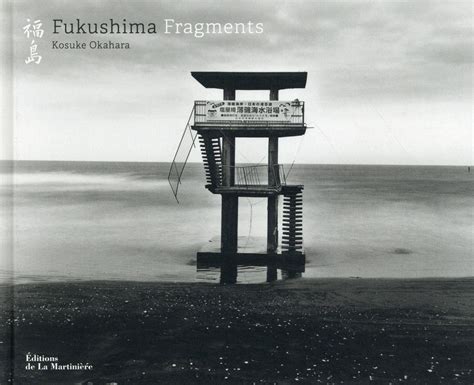

And during this lockdown, so I have the opportunity to read or reread my photo books…. And right before writing this video, I randomly released the book . Fukushima Fragments from Kosuke Okahara. He is a Japanese photojournalist, and at the time of the earthquake and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011, Okahara was in Libya to cover the conflict there.

Following the nuclear accident at the Fukushima power plant, he returned to Japan as soon as possible… in order to document events, which gives rise to this book.

In the introduction, there is a passage that struck me, which I will read to you:

“I was carrying two suitcases along with heavy photographic equipment, and worried about how to navigate from one commuter train to another during Tokyo’s extremely difficult rush hour. When I got to town, I was stunned…. The Tokyo I knew was a city drowned in bright signs, a city that never slept. The one I discovered that day was plunged into darkness and completely empty. The fear of radiation, the continuous power cuts and the jishuku a very Japanese notion of voluntary self-restriction, gave the image of a dead city. »

Of course, when you read this when the streets of your own city are deserted, and half of the world’s population is confined to their homes, it does resonate a little bit.

What Fukushima has in common with today’s crisis is, in my opinion, the invisible side of the threat.. Although the nuclear accident in Fukushima did not cause any direct deaths from radioactivity, next to the 18 079 dead and missing caused by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami, the fear is not the same.

An earthquake, a tsunami, it’s concrete, palpable. You can see the debris, and once it’s gone, it’s gone. All you have to do is cry and rebuild. But the invisible threat provokes in us a different, more animal-like fear. by definition we don’t control it, and we have only limited means to diminish its effects on us.

Visiting the Fukushima region at the time with a Geiger counter gave some grip on the reality of the threat, but deep down in our primate brains there is still doubt. And I think we’re in a similar state with the coronavirus: disinfecting our purchases and washing our hands thoroughly gives us a grip on the threat, which is real, but we’re never really sure. What if someone had sneezed 2 minutes before we went through, and we unconsciously walked through a cloud of virus? We can’t help but think about that.

Anyway, anyway, it gave me the idea of taking an interest in how the invisible threat had been dealt with in photography. Indeed, “ invisible ” and “ photographie ” by definition do not go well together.

So let’s start with the book I was just talking about, then. In Fukushima FragmentsIn spite of his job as a photojournalist, Okahara has chosen an approach that I find more personal, not in the search for the exhaustiveness of a report, but on the contrary in the translation into images of his personal feelings, while trying to open a window on reality.

He mainly photographed the absence of man in the landscape…. A few pictures show the visible damage of the tsunami, but for the majority of them, it is suddenly empty, abandoned places. The invisible threat manifests itself in its most visible aspect: the absence of Man.

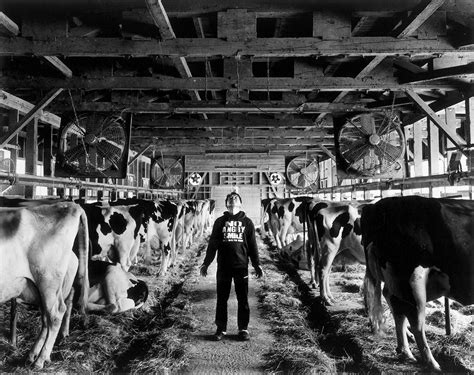

We can still see some human beings in his book, mainly the people in charge of the crisis management (clean-up, police officers in charge of controlling the area), and the people who remained on the spot, in the areas that are not very contaminated, but still uncomfortably close to the power plant.

And paradoxically, after many pages of scenery emptied of any human, The appearance of human presence in the photographs further reinforces this sense of invisible threat.. We are only spectators of the book, we don’t have the absence of the crackling of the Geiger counter to reassure us, and we can only be a little worried about them.

You may remember, but in 2016 I made a video at the Rencontres d’Arles on the work of Guillaume Bression and Carlos Ayesta.and already there I mentioned the difficulty of representing the invisible threat. I’ll put the link at the end of the video, and you’ll see that they made a very different choice, using staging in one of their series.

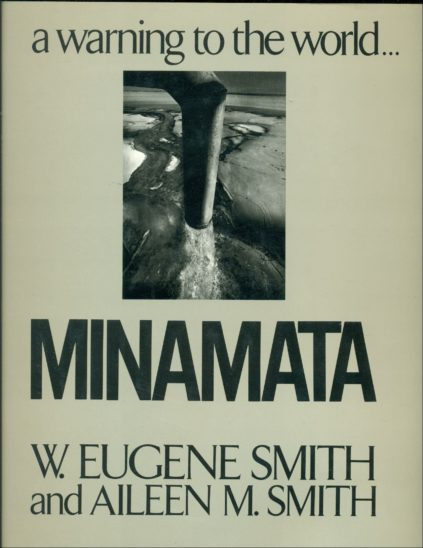

The second book I would like to talk about is “Minamata” by W. Eugene and Aileen Smith. It’s a book that dates back to 1975, in which these two photographers went to Japan, again, to document the consequences of the ecological and human disaster of Minamata Bay.

It’s such a well-known example that I saw it in ecotoxicology school.I mean, it’s a textbook case, practically.

To sum up simply, in 1907, the Chisso company set up a chemical plant in the Bay of Minamata in Japan. Beginning in 1932, it began discharging heavy metal residues, including mercury, into the bay.

This mercury derivative is absorbed by living beings and accumulates in their flesh. As it moves up the food chain, the mercury becomes more and more concentrated in the flesh of the fish, through a phenomenon called bioaccumulation. Simply put, plankton accumulates a little bit of mercury, small fish eat a lot of plankton and therefore accumulate a lot of mercury, and big fish eat a lot of small fish and therefore really accumulate a lot of mercury.

And as you can guess: humans eat a lot of big fish, and therefore accumulate really really a lot of mercury.

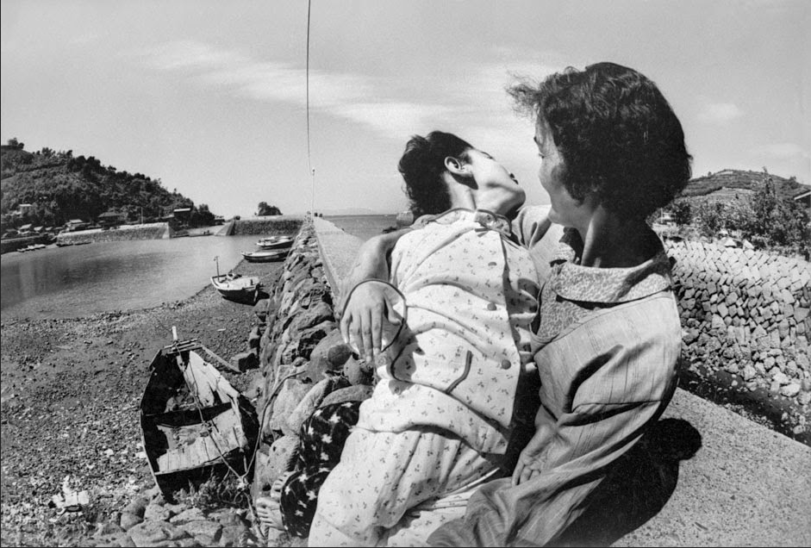

This intoxication creates what has been called Minamata disease…which results in neurological symptoms such as reduced visual field, hearing, speech, limb coordination, and fetal malformations.

It is first described in 1949, and its origin is understood in 1959 thanks to a doctor employed in Chisso. The discharges finally stop in 1966, and the disease will have affected tens of thousands of people… (Estimates are difficult so long afterwards, but 13 000 people have been recognized by the state, and 25 000 moreover are awaiting a decision).

I’ll give you a quick summary of the story, but in the book, the Smiths go much further. It’s a real photo-reportage There’s a lot of text, and the book even ends up with several pages with precise data, tables and graphs.

In their photos, the Smiths make an almost opposite choice to Okahara’s inFukushima Fragmentsthe human is omnipresent. The book is in several parts, and focuses sometimes on the public meetings with the leaders of Chisso, the families of the victims, the demonstrations, the trial, and finally a certain note of hope by showing how life goes on in spite of everything.

So they have a much closer approach to reportingwhich is probably more comprehensive and focuses more on the consequences of the invisible threat.

However, the book is not meant to be objective…. It’s even the FIRST sentence of the introduction: ” This is not an objective book.» The Smiths are aware that their discourse is passionate, and they do not seek objectivity.

I find these two rather opposite examples interesting: they show how one can try to grasp an invisible threat in completely different ways, and how the personality of the artists greatly influences the final work .

So I hope you’ve learned something from it.

I chose to talk only about these two books because they are the only ones I had on the subject, but they are obviously not the only ones that deal with an invisible threat. If you know of others, please feel free to tell us a little about them in a commentary,and tell us how the author expresses that feeling.

It will no doubt be interesting to compare this to the photographic works that will no doubt be created during this crisis.Because I don’t doubt for a moment that photographic artists all over the world have something to say about what we’re going through.and that in a little while, we can see the works, and through them we can remember and reflect on what happened.

That’s it for today! If you liked this video, remember to give it a blue thumb and share it with your friends. If you ever discover the channel with this video, remember to subscribe and click on the bell so you don’t miss the next ones, and then download your free guide to progress in pictures. Who knows, maybe one of you will produce a significant work on our situation, at least I hope so.

I’ll see you in the next video, and until then, see you soon, and good pictures!

Discussion about this post