The same type of question often comes up in the dozens of emails I receive every day: the management of indoor photography situations (in low light). Many of you encounter this common problem in photography, i.e. not having enough light to get a well exposed picture, sufficiently luminous.

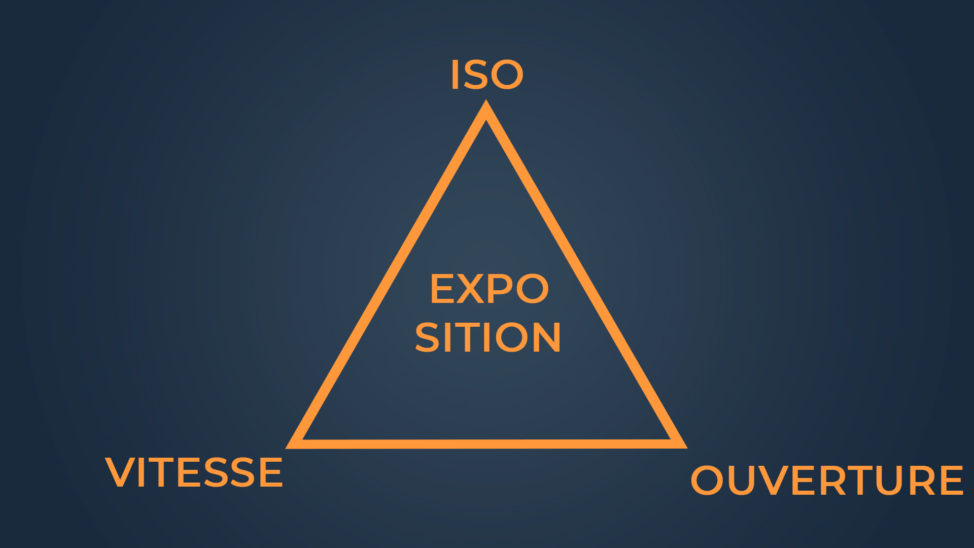

If you are already familiar with the basics of photography (including the exposure triangle), as well as the semi-automatic modes, you should be able to handle these situations. But since I often have this kind of question, it probably deserves a rewording.

So I’m going to explain to you tools at your disposal to manage this, which will allow you to improve your images, but also to know when it will be impossible to take a satisfactory photo (because no, you can’t take a photo in total darkness 😉 ).

Technical levers for indoor photography

There are not 36 solutions to deal with the problem, there are 3, which will necessarily remind you of something. If you’ve never heard of it, then you’re gonna be You have to go read my articles on the subject beforehand, as I’ll only briefly remind you below:

The opening

The first solution if you don’t have enough light indoors, it’s going to be toincrease openness used by your device. Remember that the smaller the number, the larger the aperture. This lever will come up against 2 constraints, one technical, and the other artistic.

First of all, the maximum opening you can use is limited by the maximum aperture of your lens. On compacts or bridges, there is not much you can do about it, but on SLRs and hybrids, as you can change the lens, you can influence it: choose your lens with greatest openness.

If you don’t have one that opens at least at f/2.8, it’s not necessarily going to help you much. So if you’re often blocked by a lack of light, you might consider buying a lens with a larger aperture, such as a 17-50mm f/2.8 zoom, or a 50mm f/1.8.

Then, increasing the opening will directly result in decrease the depth of fieldThis is the sharpness area on your image. In other words, to increase what is called background blur, or bokeh.

This can be a desired effect (if you want to isolate the subject from the background, for example), but if you want to have an large depth of focus (the image is sharp on all its depth), I advise you to first try to play on the 2 other factors.

But that’s why many images taken in low light have a shallow depth of field: you have to compensate for this lack of light.

Shutter speed

The second is slow down shutter speed (or exposure time) you use, which will allow more light to enter. Here, the shutter speed is only not limited by the unit (you can usually go up to 30 seconds or more in Bulb mode). But here again, this lever comes up against 2 constraints, one technical, and the other artistic.

First of all, you will not be able to slow down the shutter speed indefinitely without affecting your image. You must have already noticed this (even if the most beginners among you have not yet understood why), at too slow a speed, the image is blurred..

It’s a phenomenon called the motion blur Contrary to what you think, even if you don’t smoke and drink coffee, you are not not absolutely motionless when you’re holding your camera. At fast speeds, this movement remains imperceptible, but at slower speeds, it shows on the picture and causes a very unattractive effect.

A known and simple rule to remember is that the speed must not no slower than 1 / focal length…if you’re shooting freehand. So if you shoot at 50mm, you should at least use a speed of 1/50 (or faster, like 1/100).

That said, this focal length must be multiplied by a certain number of times depending on sensor size. For hybrids microphone 4/3you have to multiply by 2and for APS-C sensors (most DSLRs, Sony and Fuji hybrids), you have to multiply by about 1.5.

So with the same focal length (written on the lens), you will have to choose at least 1/80th on APS-C, and 1/100th on 4/3 mic, to make it very simple.

You can also place your camera on a tripodand then you won’t have a speed limit.

The artistic constraint is also linked to movement, but not to yours, to subject’s. If the camera moves, it may be blurred in the image if you use a slower speed. In a rather intuitive way, this is all the more true since :

- Shutter speed is slow (with equal subject movement).

- subject movement is fast (at equal shutter speed)

So if you want to freeze the subject’s movementyou’re not going to be able to slow down too much, and you’re not going to be able to play on that lever. Conversely, if you don’t have a moving subject, or if you want to blur it, you can use a tripod and rely on this lever only (even using a low ISO and a small aperture).

ISO sensitivity

Finally, you’re going to be able to use that last lever, which I call the “safety valve”. Indeed, it is the lever to be used in last optionwhen you’ve already used the opening at its maximum (considering the technical limit of your objective but also your possible desire to keep a great depth of field), and also the shutter speed (considering the minimum speed to avoid motion blur, the use or not of a tripod, and your desire to freeze the subject).

The downside of ISO sensitivity is that when you increase it, it will create noise in the picture. Low ISO sensitivities (up to ISO 400 or even 800) often have very reasonable noise, but beyond that, things usually start to go wrong.

You should know that It depends a lot on your device. Some cameras produce a lot of noise as early as ISO 1600 (or even less), and for others you have to wait for ISO 6400 or more to be annoyed. There is no hard and fast rule here: it’s up to you to test and see what noise is acceptable.

Caution: rate it to photo viewing size (in full screen for example), and not by zooming in at 100%, which doesn’t make sense.

Adjustment of post-treatment exposure

There is also the possibility ofincrease exposure to post-treatmentespecially if you work in RAW, which is much more flexible in this regard. Note that it will produce noise (of the grain in the picture), in the same way as increasing ISO sensitivity. So you won’t do miracles if you were already at the maximum acceptable ISO sensitivity allowed by your sensor.

That said, good RAW software usually allows for a excellent noise reduction (I’m thinking in particular of Lightroom which still amazes me on this point), and will make you gain a little more latitude.

The other levers

These purely technical levers are interesting, but there are also other ways to make things a little easier when shooting, which have nothing to do with adjustments.

Understanding light

The first is to fully understand how light works. I had already written an article on the photographic light…where I “gave voice to the light.” I strongly advise you to (re)read it, for there is no point in repeating it here.

But I can take a very simple example: if you photograph someone indoors with artificial light, a simple method can be to bring a light source closer of the subject (or to bring the subject closer to the source). It can really make the amount of light vary enormously, and thus make the difference between a failed (or impossible to take!) photo and a successful one.

Adding light with a flash

Of course, you can also decide to add light to the image, with artificial lighting, usually a flash. The flash included on your camera is terrible low power, producing a harsh light and arriving full face on your subject, it will give always an unattractive, even downright disgusting result, let’s just say it. If that’s all you’ve got, there are still some almost free ways to improve the light.

Otherwise, the best solution is probably the cobra flash. If you think about diffusing it or reflecting it in some way (by pointing it towards the ceiling, with a white cardboard, …), the result should be satisfactory after a few tries. Don’t hesitate to use it in automatic at the beginning.

To learn more, you can read the article on choosing a flash and the article on its use.

How to photograph in low light, concretely?

You’re going to tell me that this is all well and good, that you understand how it works in theory, but that you’re having trouble seeing how to put this into practice. I understand you, I had a hard time starting out, actually. But you’ll see, it’s not that complicated.

In Aperture Priority Mode (A or Av)

If you are in opening priority mode, logically, you want to control the depth of field. In this case, start by choosing the aperture you want, in relation to your photographic intention. By pressing the shutter release button halfway, the camera will display the speed he’s going to use, in the viewfinder or on the screen.

- If shutter speed is important to you (because you are shooting freehand, and/or because the subject is moving), look at it. If it is too slow, increase the ISO sensitivity. until it’s fast enough.

- If that’s not enough, you can decide to…increase openness…even if it means losing depth of field. It will change your image, but it will allow you to get the correct exposure.

- If you’re at your maximum everywhere, then you’re up against the limitations of your equipmentand I’m sorry, but you’ll have to come back !

- Note that you may want to go a little too slow if your only concern is motion blur (not subject blur): at the limit speeds, with a bit of luck and a good chock you may be able to get a sharp picture, especially if you have the stabilization.

- If the shutter speed is not important (because you are shooting on a tripod, and the subject is motionless, or you don’t care if the subject is blurry), then you are free to shoot.

In speed priority mode (S or Tv)

Here, logically, speed is important to you. If you have problems in low light, it’s probably because it’s fast, so you’d like to freeze the subject. In this case, start by choosing the speed sufficient to freeze the subject (there is no absolute rule, you have to test).

When the shutter-release button is pressed halfway down, the camera will display the aperture it will use. If it flashes (or is displayed in red, depending on the device), it means that your device will use the maximum aperture, but that it’s still not enoughand therefore the final photo will be underexposed.

In this case, you can increase the ISOs until the flashing stops the photo will be well exposed. You can also increase ISO if you want the camera to close the iris a little more (typically to gain depth of field).

If you still cannot get the correct exposure, you will reach the limitations of your equipment.

2 different school cases (and different solutions)

I’m sure that despite all these explanations, one or two concrete examples could still help you fully grasp all the implications. So let’s see it in real-world setting.

The landscape posed cushy

You are at the beach on a spring eveninga little after sunset. The sky is pretty, you have a beautiful scenery, in short, you want to take a picture. But it’s already a bit dark. But luck (finally foresight), you have your tripod in your pocket or your Mary Poppins bag!

So you can put your device on a tripodSelect a sufficient opening to have the whole net landscape (let’s say f/11). As you will be able to play with the slow shutter speed lever to the maximum, you can leave it to ISO 100. The device will decide on a certain speed, but… Anyway, you’re on a tripod.. All that’s left to do is set it off! (with the mirror lock, and a remote control or the self-timer, as a reminder)

The fast subject in low light

You are in a concert hall that smells like beer and sweat……for a good rock concert in a darkened room. Well, normally if you have a camera and the friendly and debonair security guard at the entrance hasn’t turned you away, it means you have an accreditation, so if the world is going round you don’t need my advice there.

But hey, let’s say it’s just to put the picture down, it also works if you’re trying to take a picture of grandma rock dancing in the living room on New Year’s Eve (even though it smells more like champagne and patchouli than beer and sweat, but let’s skip 😀. ).

Anyway, you have a fast subject whose movement you wish to freeze. You put yourself in priority speed, let’s say at 1/150th. At the first brush with the trigger, the little “f/2.8” flashes everywhere.

There, you increase ISOs until it stops blinking (in this case you will have a good exposure), or until the maximum acceptable sensitivity (ISO 1600 for example) is reached. If it keeps blinking, you can still take the picture, but it will be underexposed. It can make up for it if it’s not too bad, but not if it’s pitch black.

Well, I hope that this article, very focused on beginners, will help you in low light situations where you wonder how the hell you’re going to take that picture!

Discussion about this post