There are hundreds of tutorials on the Web that explain how the exposure triangle works. However, this mechanism still raises many questions among beginners in photography.

This tutorial will allow you to understand why the exposure triangle is a notion wrongly perceived as complex and will help you to better understand the mysteries of exposure.

This photo tutorial is brought to you by Jacques Croizer. Regular collaborator of Nikon Passion, he is also the author of a guide that simplifies the photo technique for the pleasure of taking pictures.

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

The majority of the cult images that make up both our repository and our photographic heritage have been produced using the manual exposure mode. This argument alone is enough to incite many beginners to switch to this mode at the slightest opportunity.

They are also trained there by multiple authors, trainers and other prescribers who continue to perpetuate a tradition in which mastery of the exhibition triangle, at the base of the manual mode, remains the essential foundation of any successful photo.

This reasoning is a little too quick to overlook the cohort of failed photos that have never made it through history, even if they were taken by Robert Capa, to mention only this emblematic figure of reportage photography, a discipline which, understandably, requires great reactivity on the part of those who practice it.

But Capa had no other choice than manual mode, since the first consumer reflex camera with automatic exposure with aperture priority only appeared in the early seventies … If you’re not Capa, you have a much more advanced equipment than it is today!

Quays of the Rhône (C) Jacques Croizer

Today the expert photographer does not choose one f-stop value rather than another because he wants to bring in more or less light, but because he is looking for more or less depth of field.

He does not select a shorter or longer exposure time because he wants to adjust the exposure of the image, but because he needs to adjust the exposure time to the shutter speed of his subject. He doesn’t want technique to restrict his creativity.

Recognizing that the spontaneity of the image is achieved by automating the exposure settings, all camera manufacturers offer two magic modes that are suitable for 90% of situations, without the need to master the complexity of the exposure triangle :

- the “speed priority” mode (S or Tv depending on the brand),

- the “opening priority” mode (A or Av according to the marks).

These semi-automatic modes allow you to choose the setting you want to interact with, with the intelligence of your camera taking care of exposing your photo correctly.

If you are not familiar with the PSAM wheel, which allows you to select the exposure mode adapted to your needs, please read this very complete tutorial.

When you’re new to photography, you don’t need the manual mode or the exposure triangle, unless you want to make your life more complicated.

Don’t conclude that manual mode is useless!

There always comes a moment when the photographer is asked to act separately on the three exposure parameters. But then he is no longer a beginner. He is used to juggling these settings for the reasons mentioned above (depth of field, sharpness, lack of light). He no longer has any trouble integrating the notion of exhibition.

Just one example to convince you of this: the studio.

You create your own light. Once you’ve found the right settings, switching to manual mode means you don’t have to worry about variations in framing that alter the average tone of the image, and thus the response of the automation. You can concentrate on your model.

If you’re new to photography, you won’t understand these explanations. It’s normal and it won’t prevent you from taking beautiful pictures!

Another criterion for using the manual mode is that newer cameras are able to increase their sensitivity without damage, which opens up new possibilities for you.

If your camera offers the “ISO Auto” option, combining it with manual mode allows you to work as if you were in both shutter speed priority and aperture priority mode: you can select the shutter speed and aperture to suit your needs, and the camera will adapt the sensitivity to properly expose the photo.

The manual mode is actually a semi-automatic mode which does not mean its name.

Be aware, however, that it is impossible to achieve a large depth of field and a very short exposure time at the same time once the light starts to fade: for example, in natural light indoors, you will not take better pictures in manual mode than in aperture-priority mode.

The space of freedom offered by the manual mode has the same limits as those to be taken into account by the semi-automatic modes.

Why is the exposure triangle so difficult to understand?

Partly because it inherits a technical vocabulary full of contradictions in the eyes of those who don’t want to dive in (and we understand them!) in the laws of optics and other mathematical arcana.

First contradiction, the trigger speed is not a speed.

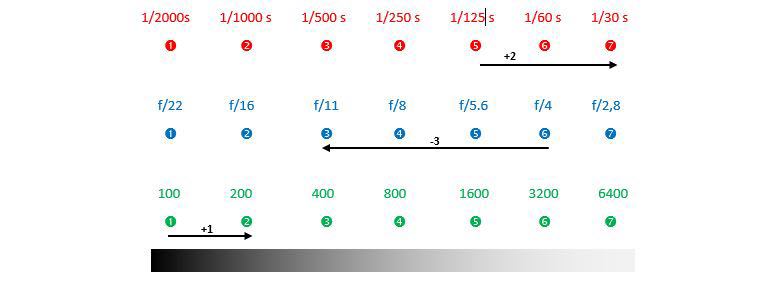

This is actually a time, the time during which the shutter lets light into the sensor. The scale is not very nice since it is graduated in fractions of a second:

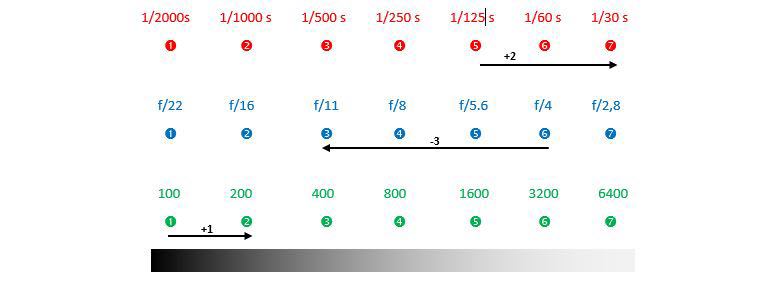

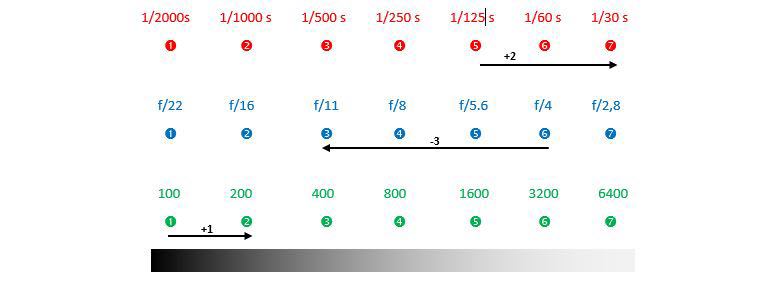

exposure triangle: the exposure time scale

Let’s use an analogy to dissect it: the more you are on the bottle, the less the glasses will be filled.

Similarly, the greater the number that characterizes the speed, the less light the sensor receives. Forget the “1/” before the number. At position 1000, the sensor receives 10 times less light than at position 100. We could simply write down each setting from 1 to 7 and say :

- go from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) always brings in twice as much light from the initial position. Changing from 1/2000 sec to 1/1000 sec therefore has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from 1/100 sec to 1/50 sec, even if these numbers are very different in absolute terms. It is not the initial light value (its passage time is 20 times less per 1/2000 sec than per 1/100 sec) but the fact that it is doubled.

- go from one notch to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) increases the risk of blurring if the subject is mobile. Your camera allows you to go far beyond 7 (1/30 sec), but it is your own shaking that can cause the picture to be blurred. Below 1/30 sec, you need to think about the tripod, which is outside the scope of a beginner’s experiment.

Let’s continue with the opening (or the diaphragm, it’s the same thing.).

It characterizes the size of the door through which the light reaches the sensor. The graduations of its scale are even darker than those used for speed :

exposure triangle: the scale of openings

The interpretation is the same. Forget the “f/” which is useless to you: the smaller the number that characterizes the diaphragm, the more light the sensor receives. The positions can again be ordered from 1 to 7, so that :

- when you move from one step to the next (in the direction of the arrow) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. This is exactly what we’ve already seen for speed. Thus, changing from f/22 to f/16 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from f/5.6 to f/4, even though the initial light quantity at f/5.6 is 4 times greater than at f/22.

- when you move from one step to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) you increase the blur around the subject: the depth of field decreases.

From the study of velocity scales and diaphragms two simple rules follow:

- the smaller the number (without worrying about the “/” sign.) and the more light you bring in,

- The smaller the number, the greater the blur, whether it is motion for speed or depth of field with the diaphragm.

Now we have to talk about the third thief in the exhibition triangle, sensitivity.

When the lighting is lacking, when the door is opened as wide as the lens allows, when the speed reaches the limit below which the photo will be blurred, in short when it is impossible to physically send more light to the sensor, the electronics come to the rescue of the photographer: they allow the light to be artificially amplified before the image is recorded.

Simply increase the ISO sensitivity. But here again, the scale is not graduated in a very natural way:

exposure triangle: the sensitivity scale

The numbers are increasing very rapidly and it’s anxiety-provoking. You’ve been told so many times that if you increase the sensitivity too much, the image will turn into a mush of pixels … (digital noise).

Times have changed: while it is true that it is useless to turn on the amplifier when there is enough light, all recent devices allow you to go up without damage to at least ISO 800 if necessary. It is always more damaging to have to brighten a photo with post-processing software than to increase the sensitivity as soon as the picture is taken in order to expose it correctly.

The scale can again be scaled from 1 to 7 so that :

- when you jump from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) it’s all happening as if (thanks to the amplifier) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. So changing from ISO 100 to ISO 200 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from ISO 1600 to ISO 3200. You know the drill!

Just to add to the confusion, we have so far positioned ourselves on the side of the sensor.

For the picture to be properly exposed, it must always receive the same amount of light, whether your subject is in a tunnel or in direct sunlight. It’s a bit like when you salt your soup: whether the salt shaker has a small hole or a large hole, it will always need the same amount of salt to make the soup taste good. If there is plenty of salt, you will let it run for less time.

An example will give you a good understanding of the principle.

You take a picture in manual mode and it’s overexposed. So the sensor received too much light. Simply increase the value of the iris or the shutter speed to correct the problem, so increase the number that characterizes either of these two parameters.

Are you still here? So you really want to get your hands on the exhibition triangle!

You will have noticed that regardless of the selected scale, it is possible to scale from 1 to 7 if you reduce the possibilities of the instrument to its most usual range of use. The number 7 indicates the position at which the sensor receives maximum light.

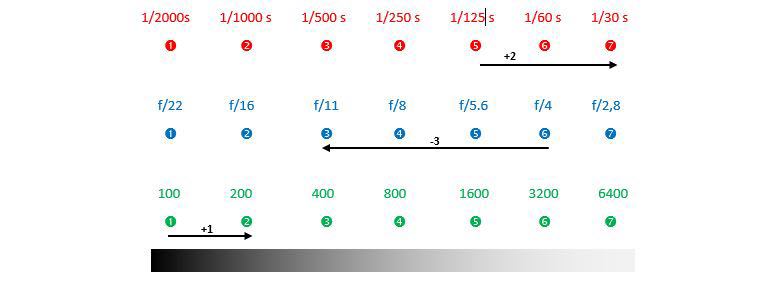

These notches are perfectly equivalent, whether on the scale of diaphragms, speed or sensitivity. Each time you move from one position to the next, in the direction of the arrow, the light reaching the sensor is doubled. As a result, moving from step 5 to step 6 on the f-stop scale (f/5.6 to f/4) brightens the image in the same way as moving from step 3 to step 4 on the shutter speed scale (1/500 s to 1/250 s) or from step 1 to step 2 on the sensitivity scale (ISO 100 to 200). Convenient, isn’t it?

It is this last notion of equivalence between the different settings that must be kept in mind:

Since each notch represents the same light variation regardless of the scale selected, any action on one scale can be compensated for by the reverse action on either of the other two remaining scales.

Let’s take an example I want to gain depth of field by closing the aperture at f/11, but my picture is correctly exposed at 1/100 s for f/4 at ISO 100.

In aperture-priority mode, the other two settings would adjust immediately. In manual mode, it’s up to me to adjust them. Here’s how to do it:

exposure triangle: how to vary aperture, exposure time and sensitivity

- the diaphragm moves from position 6 (f/4) to position 3 (f/11). I therefore lose three notches from the initial exposure. To keep my picture not too dark, I have to get them back on the other two scales. I give priority to the speed scale.

- the 1/125th of a second is position 5. I’d have to go to position 8 to get the 3 lost notches back. This position is not represented on the graph, but it exists on my camera. It’s 1/15 sec. At this speed, the picture might be blurred. I prefer to stay at 1/30 sec. So I only regained two notches.

- I’m going to find the notch I still lack on the sensitivity scale by going from ISO 100 to 200.

I didn’t have to think about it. All I had to do was count the number of graduations moved on each scale, paying attention to the direction in which I was making these variations. Don’t worry, it’s much easier to do with the box in hand than to read these explanations!

Start with the two scales of speed and diaphragm. They vary in the same direction, so if you increase the number on one scale, you must decrease it on the other scale.

If you are forced to exceed position 7 on either of these two scales, report the missing increase on the sensitivity scale. The reverse is obviously true if you reach the stop on the 1 of the diaphragm or speed scale. In this case, the sensitivity must be decreased.

I’m sure you want to try! On your device, the variations may be half or a third of a notch. It doesn’t matter, the rule is always the same: the three variations combined must have a sum:

- zero if you want to get the same exposure as with the automatic,

- positive if you want to brighten the picture,

- negative if not.

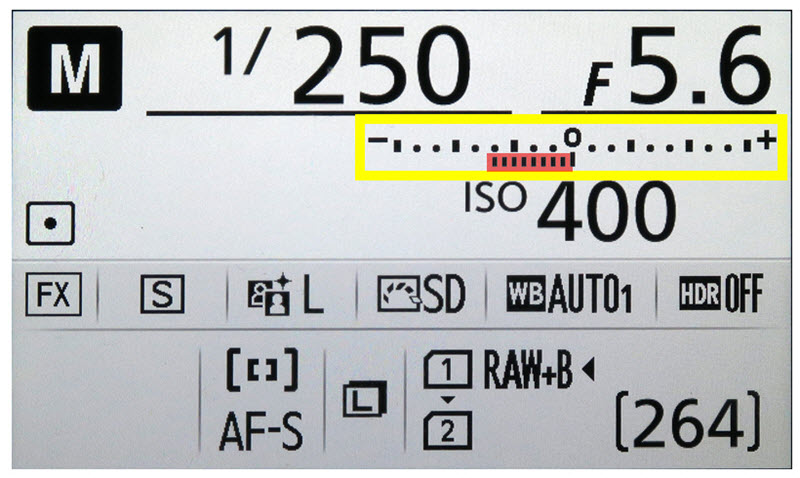

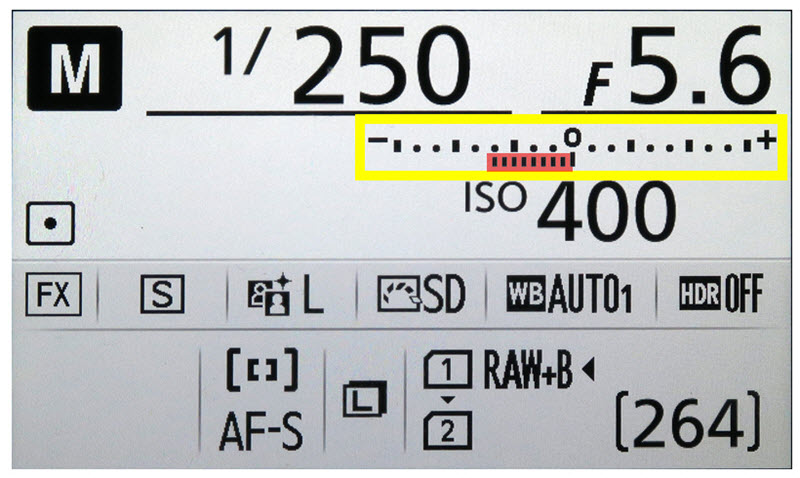

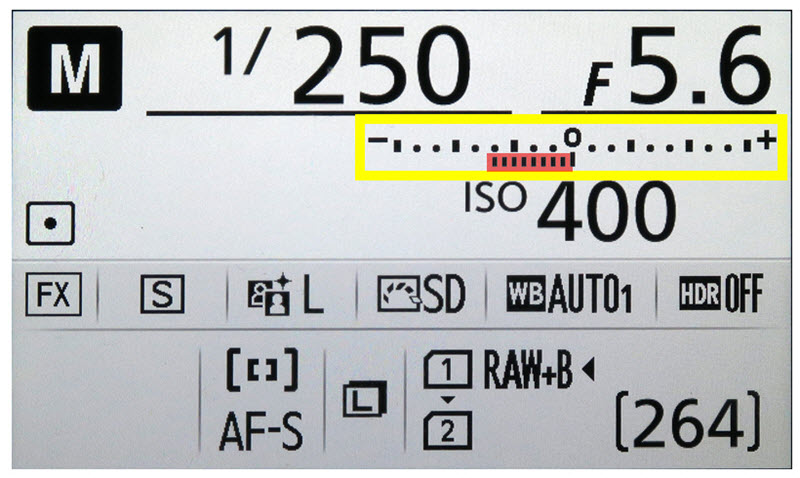

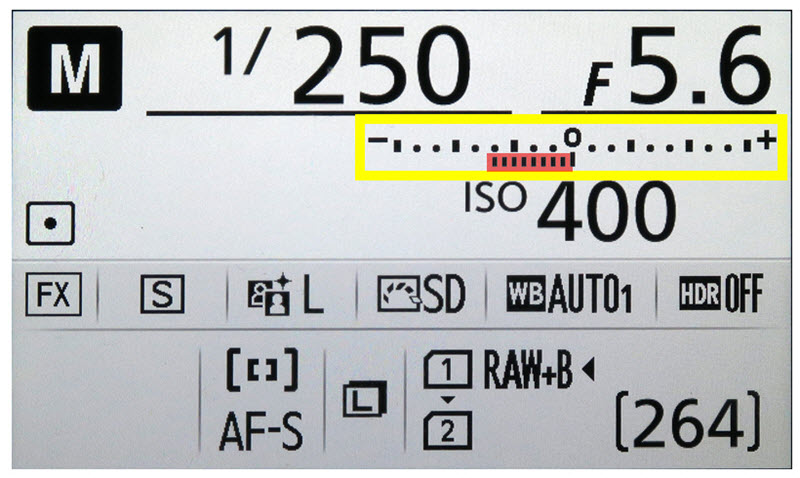

A gauge on the back of your case or in the viewfinder allows you to see how your adjustment is positioned in relation to the central position, the one that the automatic system would have chosen. Be careful, it moves only if you are in manual mode!

exposure triangle: the display of the exposure in the viewfinder of a Nikon reflex camera

To conclude, try this little test that will allow you to know if this tutorial has achieved its goal: to de-dramatize the exhibition triangle!

Question 1: Which of these three settings is not equivalent to the other two?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/60 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/8 | 1/30 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

Question 2: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to photograph a landscape at wide angle?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/11 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/11 | 1/100 s | 200 ISO |

Question 3: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to make a portrait that stands out well indoors against a blurred background?

| A | f/4 | 1/15 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

| C | f/4 | 1/100 s | 800 ISO |

Question 4: Setting A gives me a picture that is too bright. Which of the 2 others should I choose to darken it?

| A | f/8 | 1/250 s | 200 ISO |

| B | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 100 |

| C | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

Question 5: Which of these three settings is the best?

| A | f/2,8 | 1/500 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/11 | 1/1000 s | ISO 3200 |

| C | f/8 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

Question 1

A and B are equivalent (-1 on the diaphragm and +1 on the velocity). C is +1 on the diaphragm, +1 on the speed but only -1 on the sensitivity. With setting C, the picture will be clearer.

Question 2

The 3 settings are equivalent in terms of light. To have a large depth of field, you must close the iris. The answer would then be B or C. But why increase the sensitivity when 1/100 s allows you to take a sharp picture? So the best answer is C.

Question 3

The open f/4 f-stop gives a blurred background with the 3 settings which are otherwise equivalent in terms of light.

At setting A, the subject may be blurred because the shutter speed is too low.

Answer B would be suitable for a still subject, but when you’re doing a portrait, you’re close to your model (between 2 and 3 meters) which amplifies the movements. If possible, it is better to increase the speed to avoid blurred movement.

The answer C is therefore the best. 800 ISO is not the end of the world!

Question 4

Settings A and C send the same amount of light to the sensor. The correct answer is B. This setting is two notches below the other two.

Question 5

Don’t tell me you’ve answered that nonsensical question? There is no such thing as a “right setting” in absolute terms. You always have to consider the situation.

The A setting leads to a very small depth of field, especially if you are close to your subject, but perhaps you are looking for a smooth bokeh?

Response B uses a very high sensitivity. It is suitable for a fast-moving subject for which you need a large depth of field.

The answer C is well balanced, but the speed will be insufficient if your subject is moving fast, and the depth of field will be too great if you expect a blurred background.

In short, there is no good answer to this question!

If you got 5 correct answers, you have mastered the exposure triangle perfectly.

Between 3 and 4 correct answers, you’re a little distracted. Any inattention error will result in a poorly exposed photo.

If you have between 1 and 2 correct answers, the author of this article has missed something!

Use the comment box below to ask questions that will help us make this tutorial clearer. In the meantime, you have plenty of fun with the semi-automatic modes!

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

There are hundreds of tutorials on the Web that explain how the exposure triangle works. However, this mechanism still raises many questions among beginners in photography.

This tutorial will allow you to understand why the exposure triangle is a notion wrongly perceived as complex and will help you to better understand the mysteries of exposure.

This photo tutorial is brought to you by Jacques Croizer. Regular collaborator of Nikon Passion, he is also the author of a guide that simplifies the photo technique for the pleasure of taking pictures.

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

The majority of the cult images that make up both our repository and our photographic heritage have been produced using the manual exposure mode. This argument alone is enough to incite many beginners to switch to this mode at the slightest opportunity.

They are also trained there by multiple authors, trainers and other prescribers who continue to perpetuate a tradition in which mastery of the exhibition triangle, at the base of the manual mode, remains the essential foundation of any successful photo.

This reasoning is a little too quick to overlook the cohort of failed photos that have never made it through history, even if they were taken by Robert Capa, to mention only this emblematic figure of reportage photography, a discipline which, understandably, requires great reactivity on the part of those who practice it.

But Capa had no other choice than manual mode, since the first consumer reflex camera with automatic exposure with aperture priority only appeared in the early seventies … If you’re not Capa, you have a much more advanced equipment than it is today!

Quays of the Rhône (C) Jacques Croizer

Today the expert photographer does not choose one f-stop value rather than another because he wants to bring in more or less light, but because he is looking for more or less depth of field.

He does not select a shorter or longer exposure time because he wants to adjust the exposure of the image, but because he needs to adjust the exposure time to the shutter speed of his subject. He doesn’t want technique to restrict his creativity.

Recognizing that the spontaneity of the image is achieved by automating the exposure settings, all camera manufacturers offer two magic modes that are suitable for 90% of situations, without the need to master the complexity of the exposure triangle :

- the “speed priority” mode (S or Tv depending on the brand),

- the “opening priority” mode (A or Av according to the marks).

These semi-automatic modes allow you to choose the setting you want to interact with, with the intelligence of your camera taking care of exposing your photo correctly.

If you are not familiar with the PSAM wheel, which allows you to select the exposure mode adapted to your needs, please read this very complete tutorial.

When you’re new to photography, you don’t need the manual mode or the exposure triangle, unless you want to make your life more complicated.

Don’t conclude that manual mode is useless!

There always comes a moment when the photographer is asked to act separately on the three exposure parameters. But then he is no longer a beginner. He is used to juggling these settings for the reasons mentioned above (depth of field, sharpness, lack of light). He no longer has any trouble integrating the notion of exhibition.

Just one example to convince you of this: the studio.

You create your own light. Once you’ve found the right settings, switching to manual mode means you don’t have to worry about variations in framing that alter the average tone of the image, and thus the response of the automation. You can concentrate on your model.

If you’re new to photography, you won’t understand these explanations. It’s normal and it won’t prevent you from taking beautiful pictures!

Another criterion for using the manual mode is that newer cameras are able to increase their sensitivity without damage, which opens up new possibilities for you.

If your camera offers the “ISO Auto” option, combining it with manual mode allows you to work as if you were in both shutter speed priority and aperture priority mode: you can select the shutter speed and aperture to suit your needs, and the camera will adapt the sensitivity to properly expose the photo.

The manual mode is actually a semi-automatic mode which does not mean its name.

Be aware, however, that it is impossible to achieve a large depth of field and a very short exposure time at the same time once the light starts to fade: for example, in natural light indoors, you will not take better pictures in manual mode than in aperture-priority mode.

The space of freedom offered by the manual mode has the same limits as those to be taken into account by the semi-automatic modes.

Why is the exposure triangle so difficult to understand?

Partly because it inherits a technical vocabulary full of contradictions in the eyes of those who don’t want to dive in (and we understand them!) in the laws of optics and other mathematical arcana.

First contradiction, the trigger speed is not a speed.

This is actually a time, the time during which the shutter lets light into the sensor. The scale is not very nice since it is graduated in fractions of a second:

exposure triangle: the exposure time scale

Let’s use an analogy to dissect it: the more you are on the bottle, the less the glasses will be filled.

Similarly, the greater the number that characterizes the speed, the less light the sensor receives. Forget the “1/” before the number. At position 1000, the sensor receives 10 times less light than at position 100. We could simply write down each setting from 1 to 7 and say :

- go from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) always brings in twice as much light from the initial position. Changing from 1/2000 sec to 1/1000 sec therefore has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from 1/100 sec to 1/50 sec, even if these numbers are very different in absolute terms. It is not the initial light value (its passage time is 20 times less per 1/2000 sec than per 1/100 sec) but the fact that it is doubled.

- go from one notch to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) increases the risk of blurring if the subject is mobile. Your camera allows you to go far beyond 7 (1/30 sec), but it is your own shaking that can cause the picture to be blurred. Below 1/30 sec, you need to think about the tripod, which is outside the scope of a beginner’s experiment.

Let’s continue with the opening (or the diaphragm, it’s the same thing.).

It characterizes the size of the door through which the light reaches the sensor. The graduations of its scale are even darker than those used for speed :

exposure triangle: the scale of openings

The interpretation is the same. Forget the “f/” which is useless to you: the smaller the number that characterizes the diaphragm, the more light the sensor receives. The positions can again be ordered from 1 to 7, so that :

- when you move from one step to the next (in the direction of the arrow) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. This is exactly what we’ve already seen for speed. Thus, changing from f/22 to f/16 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from f/5.6 to f/4, even though the initial light quantity at f/5.6 is 4 times greater than at f/22.

- when you move from one step to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) you increase the blur around the subject: the depth of field decreases.

From the study of velocity scales and diaphragms two simple rules follow:

- the smaller the number (without worrying about the “/” sign.) and the more light you bring in,

- The smaller the number, the greater the blur, whether it is motion for speed or depth of field with the diaphragm.

Now we have to talk about the third thief in the exhibition triangle, sensitivity.

When the lighting is lacking, when the door is opened as wide as the lens allows, when the speed reaches the limit below which the photo will be blurred, in short when it is impossible to physically send more light to the sensor, the electronics come to the rescue of the photographer: they allow the light to be artificially amplified before the image is recorded.

Simply increase the ISO sensitivity. But here again, the scale is not graduated in a very natural way:

exposure triangle: the sensitivity scale

The numbers are increasing very rapidly and it’s anxiety-provoking. You’ve been told so many times that if you increase the sensitivity too much, the image will turn into a mush of pixels … (digital noise).

Times have changed: while it is true that it is useless to turn on the amplifier when there is enough light, all recent devices allow you to go up without damage to at least ISO 800 if necessary. It is always more damaging to have to brighten a photo with post-processing software than to increase the sensitivity as soon as the picture is taken in order to expose it correctly.

The scale can again be scaled from 1 to 7 so that :

- when you jump from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) it’s all happening as if (thanks to the amplifier) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. So changing from ISO 100 to ISO 200 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from ISO 1600 to ISO 3200. You know the drill!

Just to add to the confusion, we have so far positioned ourselves on the side of the sensor.

For the picture to be properly exposed, it must always receive the same amount of light, whether your subject is in a tunnel or in direct sunlight. It’s a bit like when you salt your soup: whether the salt shaker has a small hole or a large hole, it will always need the same amount of salt to make the soup taste good. If there is plenty of salt, you will let it run for less time.

An example will give you a good understanding of the principle.

You take a picture in manual mode and it’s overexposed. So the sensor received too much light. Simply increase the value of the iris or the shutter speed to correct the problem, so increase the number that characterizes either of these two parameters.

Are you still here? So you really want to get your hands on the exhibition triangle!

You will have noticed that regardless of the selected scale, it is possible to scale from 1 to 7 if you reduce the possibilities of the instrument to its most usual range of use. The number 7 indicates the position at which the sensor receives maximum light.

These notches are perfectly equivalent, whether on the scale of diaphragms, speed or sensitivity. Each time you move from one position to the next, in the direction of the arrow, the light reaching the sensor is doubled. As a result, moving from step 5 to step 6 on the f-stop scale (f/5.6 to f/4) brightens the image in the same way as moving from step 3 to step 4 on the shutter speed scale (1/500 s to 1/250 s) or from step 1 to step 2 on the sensitivity scale (ISO 100 to 200). Convenient, isn’t it?

It is this last notion of equivalence between the different settings that must be kept in mind:

Since each notch represents the same light variation regardless of the scale selected, any action on one scale can be compensated for by the reverse action on either of the other two remaining scales.

Let’s take an example I want to gain depth of field by closing the aperture at f/11, but my picture is correctly exposed at 1/100 s for f/4 at ISO 100.

In aperture-priority mode, the other two settings would adjust immediately. In manual mode, it’s up to me to adjust them. Here’s how to do it:

exposure triangle: how to vary aperture, exposure time and sensitivity

- the diaphragm moves from position 6 (f/4) to position 3 (f/11). I therefore lose three notches from the initial exposure. To keep my picture not too dark, I have to get them back on the other two scales. I give priority to the speed scale.

- the 1/125th of a second is position 5. I’d have to go to position 8 to get the 3 lost notches back. This position is not represented on the graph, but it exists on my camera. It’s 1/15 sec. At this speed, the picture might be blurred. I prefer to stay at 1/30 sec. So I only regained two notches.

- I’m going to find the notch I still lack on the sensitivity scale by going from ISO 100 to 200.

I didn’t have to think about it. All I had to do was count the number of graduations moved on each scale, paying attention to the direction in which I was making these variations. Don’t worry, it’s much easier to do with the box in hand than to read these explanations!

Start with the two scales of speed and diaphragm. They vary in the same direction, so if you increase the number on one scale, you must decrease it on the other scale.

If you are forced to exceed position 7 on either of these two scales, report the missing increase on the sensitivity scale. The reverse is obviously true if you reach the stop on the 1 of the diaphragm or speed scale. In this case, the sensitivity must be decreased.

I’m sure you want to try! On your device, the variations may be half or a third of a notch. It doesn’t matter, the rule is always the same: the three variations combined must have a sum:

- zero if you want to get the same exposure as with the automatic,

- positive if you want to brighten the picture,

- negative if not.

A gauge on the back of your case or in the viewfinder allows you to see how your adjustment is positioned in relation to the central position, the one that the automatic system would have chosen. Be careful, it moves only if you are in manual mode!

exposure triangle: the display of the exposure in the viewfinder of a Nikon reflex camera

To conclude, try this little test that will allow you to know if this tutorial has achieved its goal: to de-dramatize the exhibition triangle!

Question 1: Which of these three settings is not equivalent to the other two?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/60 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/8 | 1/30 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

Question 2: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to photograph a landscape at wide angle?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/11 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/11 | 1/100 s | 200 ISO |

Question 3: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to make a portrait that stands out well indoors against a blurred background?

| A | f/4 | 1/15 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

| C | f/4 | 1/100 s | 800 ISO |

Question 4: Setting A gives me a picture that is too bright. Which of the 2 others should I choose to darken it?

| A | f/8 | 1/250 s | 200 ISO |

| B | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 100 |

| C | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

Question 5: Which of these three settings is the best?

| A | f/2,8 | 1/500 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/11 | 1/1000 s | ISO 3200 |

| C | f/8 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

Question 1

A and B are equivalent (-1 on the diaphragm and +1 on the velocity). C is +1 on the diaphragm, +1 on the speed but only -1 on the sensitivity. With setting C, the picture will be clearer.

Question 2

The 3 settings are equivalent in terms of light. To have a large depth of field, you must close the iris. The answer would then be B or C. But why increase the sensitivity when 1/100 s allows you to take a sharp picture? So the best answer is C.

Question 3

The open f/4 f-stop gives a blurred background with the 3 settings which are otherwise equivalent in terms of light.

At setting A, the subject may be blurred because the shutter speed is too low.

Answer B would be suitable for a still subject, but when you’re doing a portrait, you’re close to your model (between 2 and 3 meters) which amplifies the movements. If possible, it is better to increase the speed to avoid blurred movement.

The answer C is therefore the best. 800 ISO is not the end of the world!

Question 4

Settings A and C send the same amount of light to the sensor. The correct answer is B. This setting is two notches below the other two.

Question 5

Don’t tell me you’ve answered that nonsensical question? There is no such thing as a “right setting” in absolute terms. You always have to consider the situation.

The A setting leads to a very small depth of field, especially if you are close to your subject, but perhaps you are looking for a smooth bokeh?

Response B uses a very high sensitivity. It is suitable for a fast-moving subject for which you need a large depth of field.

The answer C is well balanced, but the speed will be insufficient if your subject is moving fast, and the depth of field will be too great if you expect a blurred background.

In short, there is no good answer to this question!

If you got 5 correct answers, you have mastered the exposure triangle perfectly.

Between 3 and 4 correct answers, you’re a little distracted. Any inattention error will result in a poorly exposed photo.

If you have between 1 and 2 correct answers, the author of this article has missed something!

Use the comment box below to ask questions that will help us make this tutorial clearer. In the meantime, you have plenty of fun with the semi-automatic modes!

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

There are hundreds of tutorials on the Web that explain how the exposure triangle works. However, this mechanism still raises many questions among beginners in photography.

This tutorial will allow you to understand why the exposure triangle is a notion wrongly perceived as complex and will help you to better understand the mysteries of exposure.

This photo tutorial is brought to you by Jacques Croizer. Regular collaborator of Nikon Passion, he is also the author of a guide that simplifies the photo technique for the pleasure of taking pictures.

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

The majority of the cult images that make up both our repository and our photographic heritage have been produced using the manual exposure mode. This argument alone is enough to incite many beginners to switch to this mode at the slightest opportunity.

They are also trained there by multiple authors, trainers and other prescribers who continue to perpetuate a tradition in which mastery of the exhibition triangle, at the base of the manual mode, remains the essential foundation of any successful photo.

This reasoning is a little too quick to overlook the cohort of failed photos that have never made it through history, even if they were taken by Robert Capa, to mention only this emblematic figure of reportage photography, a discipline which, understandably, requires great reactivity on the part of those who practice it.

But Capa had no other choice than manual mode, since the first consumer reflex camera with automatic exposure with aperture priority only appeared in the early seventies … If you’re not Capa, you have a much more advanced equipment than it is today!

Quays of the Rhône (C) Jacques Croizer

Today the expert photographer does not choose one f-stop value rather than another because he wants to bring in more or less light, but because he is looking for more or less depth of field.

He does not select a shorter or longer exposure time because he wants to adjust the exposure of the image, but because he needs to adjust the exposure time to the shutter speed of his subject. He doesn’t want technique to restrict his creativity.

Recognizing that the spontaneity of the image is achieved by automating the exposure settings, all camera manufacturers offer two magic modes that are suitable for 90% of situations, without the need to master the complexity of the exposure triangle :

- the “speed priority” mode (S or Tv depending on the brand),

- the “opening priority” mode (A or Av according to the marks).

These semi-automatic modes allow you to choose the setting you want to interact with, with the intelligence of your camera taking care of exposing your photo correctly.

If you are not familiar with the PSAM wheel, which allows you to select the exposure mode adapted to your needs, please read this very complete tutorial.

When you’re new to photography, you don’t need the manual mode or the exposure triangle, unless you want to make your life more complicated.

Don’t conclude that manual mode is useless!

There always comes a moment when the photographer is asked to act separately on the three exposure parameters. But then he is no longer a beginner. He is used to juggling these settings for the reasons mentioned above (depth of field, sharpness, lack of light). He no longer has any trouble integrating the notion of exhibition.

Just one example to convince you of this: the studio.

You create your own light. Once you’ve found the right settings, switching to manual mode means you don’t have to worry about variations in framing that alter the average tone of the image, and thus the response of the automation. You can concentrate on your model.

If you’re new to photography, you won’t understand these explanations. It’s normal and it won’t prevent you from taking beautiful pictures!

Another criterion for using the manual mode is that newer cameras are able to increase their sensitivity without damage, which opens up new possibilities for you.

If your camera offers the “ISO Auto” option, combining it with manual mode allows you to work as if you were in both shutter speed priority and aperture priority mode: you can select the shutter speed and aperture to suit your needs, and the camera will adapt the sensitivity to properly expose the photo.

The manual mode is actually a semi-automatic mode which does not mean its name.

Be aware, however, that it is impossible to achieve a large depth of field and a very short exposure time at the same time once the light starts to fade: for example, in natural light indoors, you will not take better pictures in manual mode than in aperture-priority mode.

The space of freedom offered by the manual mode has the same limits as those to be taken into account by the semi-automatic modes.

Why is the exposure triangle so difficult to understand?

Partly because it inherits a technical vocabulary full of contradictions in the eyes of those who don’t want to dive in (and we understand them!) in the laws of optics and other mathematical arcana.

First contradiction, the trigger speed is not a speed.

This is actually a time, the time during which the shutter lets light into the sensor. The scale is not very nice since it is graduated in fractions of a second:

exposure triangle: the exposure time scale

Let’s use an analogy to dissect it: the more you are on the bottle, the less the glasses will be filled.

Similarly, the greater the number that characterizes the speed, the less light the sensor receives. Forget the “1/” before the number. At position 1000, the sensor receives 10 times less light than at position 100. We could simply write down each setting from 1 to 7 and say :

- go from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) always brings in twice as much light from the initial position. Changing from 1/2000 sec to 1/1000 sec therefore has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from 1/100 sec to 1/50 sec, even if these numbers are very different in absolute terms. It is not the initial light value (its passage time is 20 times less per 1/2000 sec than per 1/100 sec) but the fact that it is doubled.

- go from one notch to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) increases the risk of blurring if the subject is mobile. Your camera allows you to go far beyond 7 (1/30 sec), but it is your own shaking that can cause the picture to be blurred. Below 1/30 sec, you need to think about the tripod, which is outside the scope of a beginner’s experiment.

Let’s continue with the opening (or the diaphragm, it’s the same thing.).

It characterizes the size of the door through which the light reaches the sensor. The graduations of its scale are even darker than those used for speed :

exposure triangle: the scale of openings

The interpretation is the same. Forget the “f/” which is useless to you: the smaller the number that characterizes the diaphragm, the more light the sensor receives. The positions can again be ordered from 1 to 7, so that :

- when you move from one step to the next (in the direction of the arrow) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. This is exactly what we’ve already seen for speed. Thus, changing from f/22 to f/16 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from f/5.6 to f/4, even though the initial light quantity at f/5.6 is 4 times greater than at f/22.

- when you move from one step to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) you increase the blur around the subject: the depth of field decreases.

From the study of velocity scales and diaphragms two simple rules follow:

- the smaller the number (without worrying about the “/” sign.) and the more light you bring in,

- The smaller the number, the greater the blur, whether it is motion for speed or depth of field with the diaphragm.

Now we have to talk about the third thief in the exhibition triangle, sensitivity.

When the lighting is lacking, when the door is opened as wide as the lens allows, when the speed reaches the limit below which the photo will be blurred, in short when it is impossible to physically send more light to the sensor, the electronics come to the rescue of the photographer: they allow the light to be artificially amplified before the image is recorded.

Simply increase the ISO sensitivity. But here again, the scale is not graduated in a very natural way:

exposure triangle: the sensitivity scale

The numbers are increasing very rapidly and it’s anxiety-provoking. You’ve been told so many times that if you increase the sensitivity too much, the image will turn into a mush of pixels … (digital noise).

Times have changed: while it is true that it is useless to turn on the amplifier when there is enough light, all recent devices allow you to go up without damage to at least ISO 800 if necessary. It is always more damaging to have to brighten a photo with post-processing software than to increase the sensitivity as soon as the picture is taken in order to expose it correctly.

The scale can again be scaled from 1 to 7 so that :

- when you jump from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) it’s all happening as if (thanks to the amplifier) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. So changing from ISO 100 to ISO 200 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from ISO 1600 to ISO 3200. You know the drill!

Just to add to the confusion, we have so far positioned ourselves on the side of the sensor.

For the picture to be properly exposed, it must always receive the same amount of light, whether your subject is in a tunnel or in direct sunlight. It’s a bit like when you salt your soup: whether the salt shaker has a small hole or a large hole, it will always need the same amount of salt to make the soup taste good. If there is plenty of salt, you will let it run for less time.

An example will give you a good understanding of the principle.

You take a picture in manual mode and it’s overexposed. So the sensor received too much light. Simply increase the value of the iris or the shutter speed to correct the problem, so increase the number that characterizes either of these two parameters.

Are you still here? So you really want to get your hands on the exhibition triangle!

You will have noticed that regardless of the selected scale, it is possible to scale from 1 to 7 if you reduce the possibilities of the instrument to its most usual range of use. The number 7 indicates the position at which the sensor receives maximum light.

These notches are perfectly equivalent, whether on the scale of diaphragms, speed or sensitivity. Each time you move from one position to the next, in the direction of the arrow, the light reaching the sensor is doubled. As a result, moving from step 5 to step 6 on the f-stop scale (f/5.6 to f/4) brightens the image in the same way as moving from step 3 to step 4 on the shutter speed scale (1/500 s to 1/250 s) or from step 1 to step 2 on the sensitivity scale (ISO 100 to 200). Convenient, isn’t it?

It is this last notion of equivalence between the different settings that must be kept in mind:

Since each notch represents the same light variation regardless of the scale selected, any action on one scale can be compensated for by the reverse action on either of the other two remaining scales.

Let’s take an example I want to gain depth of field by closing the aperture at f/11, but my picture is correctly exposed at 1/100 s for f/4 at ISO 100.

In aperture-priority mode, the other two settings would adjust immediately. In manual mode, it’s up to me to adjust them. Here’s how to do it:

exposure triangle: how to vary aperture, exposure time and sensitivity

- the diaphragm moves from position 6 (f/4) to position 3 (f/11). I therefore lose three notches from the initial exposure. To keep my picture not too dark, I have to get them back on the other two scales. I give priority to the speed scale.

- the 1/125th of a second is position 5. I’d have to go to position 8 to get the 3 lost notches back. This position is not represented on the graph, but it exists on my camera. It’s 1/15 sec. At this speed, the picture might be blurred. I prefer to stay at 1/30 sec. So I only regained two notches.

- I’m going to find the notch I still lack on the sensitivity scale by going from ISO 100 to 200.

I didn’t have to think about it. All I had to do was count the number of graduations moved on each scale, paying attention to the direction in which I was making these variations. Don’t worry, it’s much easier to do with the box in hand than to read these explanations!

Start with the two scales of speed and diaphragm. They vary in the same direction, so if you increase the number on one scale, you must decrease it on the other scale.

If you are forced to exceed position 7 on either of these two scales, report the missing increase on the sensitivity scale. The reverse is obviously true if you reach the stop on the 1 of the diaphragm or speed scale. In this case, the sensitivity must be decreased.

I’m sure you want to try! On your device, the variations may be half or a third of a notch. It doesn’t matter, the rule is always the same: the three variations combined must have a sum:

- zero if you want to get the same exposure as with the automatic,

- positive if you want to brighten the picture,

- negative if not.

A gauge on the back of your case or in the viewfinder allows you to see how your adjustment is positioned in relation to the central position, the one that the automatic system would have chosen. Be careful, it moves only if you are in manual mode!

exposure triangle: the display of the exposure in the viewfinder of a Nikon reflex camera

To conclude, try this little test that will allow you to know if this tutorial has achieved its goal: to de-dramatize the exhibition triangle!

Question 1: Which of these three settings is not equivalent to the other two?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/60 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/8 | 1/30 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

Question 2: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to photograph a landscape at wide angle?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/11 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/11 | 1/100 s | 200 ISO |

Question 3: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to make a portrait that stands out well indoors against a blurred background?

| A | f/4 | 1/15 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

| C | f/4 | 1/100 s | 800 ISO |

Question 4: Setting A gives me a picture that is too bright. Which of the 2 others should I choose to darken it?

| A | f/8 | 1/250 s | 200 ISO |

| B | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 100 |

| C | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

Question 5: Which of these three settings is the best?

| A | f/2,8 | 1/500 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/11 | 1/1000 s | ISO 3200 |

| C | f/8 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

Question 1

A and B are equivalent (-1 on the diaphragm and +1 on the velocity). C is +1 on the diaphragm, +1 on the speed but only -1 on the sensitivity. With setting C, the picture will be clearer.

Question 2

The 3 settings are equivalent in terms of light. To have a large depth of field, you must close the iris. The answer would then be B or C. But why increase the sensitivity when 1/100 s allows you to take a sharp picture? So the best answer is C.

Question 3

The open f/4 f-stop gives a blurred background with the 3 settings which are otherwise equivalent in terms of light.

At setting A, the subject may be blurred because the shutter speed is too low.

Answer B would be suitable for a still subject, but when you’re doing a portrait, you’re close to your model (between 2 and 3 meters) which amplifies the movements. If possible, it is better to increase the speed to avoid blurred movement.

The answer C is therefore the best. 800 ISO is not the end of the world!

Question 4

Settings A and C send the same amount of light to the sensor. The correct answer is B. This setting is two notches below the other two.

Question 5

Don’t tell me you’ve answered that nonsensical question? There is no such thing as a “right setting” in absolute terms. You always have to consider the situation.

The A setting leads to a very small depth of field, especially if you are close to your subject, but perhaps you are looking for a smooth bokeh?

Response B uses a very high sensitivity. It is suitable for a fast-moving subject for which you need a large depth of field.

The answer C is well balanced, but the speed will be insufficient if your subject is moving fast, and the depth of field will be too great if you expect a blurred background.

In short, there is no good answer to this question!

If you got 5 correct answers, you have mastered the exposure triangle perfectly.

Between 3 and 4 correct answers, you’re a little distracted. Any inattention error will result in a poorly exposed photo.

If you have between 1 and 2 correct answers, the author of this article has missed something!

Use the comment box below to ask questions that will help us make this tutorial clearer. In the meantime, you have plenty of fun with the semi-automatic modes!

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

There are hundreds of tutorials on the Web that explain how the exposure triangle works. However, this mechanism still raises many questions among beginners in photography.

This tutorial will allow you to understand why the exposure triangle is a notion wrongly perceived as complex and will help you to better understand the mysteries of exposure.

This photo tutorial is brought to you by Jacques Croizer. Regular collaborator of Nikon Passion, he is also the author of a guide that simplifies the photo technique for the pleasure of taking pictures.

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

The majority of the cult images that make up both our repository and our photographic heritage have been produced using the manual exposure mode. This argument alone is enough to incite many beginners to switch to this mode at the slightest opportunity.

They are also trained there by multiple authors, trainers and other prescribers who continue to perpetuate a tradition in which mastery of the exhibition triangle, at the base of the manual mode, remains the essential foundation of any successful photo.

This reasoning is a little too quick to overlook the cohort of failed photos that have never made it through history, even if they were taken by Robert Capa, to mention only this emblematic figure of reportage photography, a discipline which, understandably, requires great reactivity on the part of those who practice it.

But Capa had no other choice than manual mode, since the first consumer reflex camera with automatic exposure with aperture priority only appeared in the early seventies … If you’re not Capa, you have a much more advanced equipment than it is today!

Quays of the Rhône (C) Jacques Croizer

Today the expert photographer does not choose one f-stop value rather than another because he wants to bring in more or less light, but because he is looking for more or less depth of field.

He does not select a shorter or longer exposure time because he wants to adjust the exposure of the image, but because he needs to adjust the exposure time to the shutter speed of his subject. He doesn’t want technique to restrict his creativity.

Recognizing that the spontaneity of the image is achieved by automating the exposure settings, all camera manufacturers offer two magic modes that are suitable for 90% of situations, without the need to master the complexity of the exposure triangle :

- the “speed priority” mode (S or Tv depending on the brand),

- the “opening priority” mode (A or Av according to the marks).

These semi-automatic modes allow you to choose the setting you want to interact with, with the intelligence of your camera taking care of exposing your photo correctly.

If you are not familiar with the PSAM wheel, which allows you to select the exposure mode adapted to your needs, please read this very complete tutorial.

When you’re new to photography, you don’t need the manual mode or the exposure triangle, unless you want to make your life more complicated.

Don’t conclude that manual mode is useless!

There always comes a moment when the photographer is asked to act separately on the three exposure parameters. But then he is no longer a beginner. He is used to juggling these settings for the reasons mentioned above (depth of field, sharpness, lack of light). He no longer has any trouble integrating the notion of exhibition.

Just one example to convince you of this: the studio.

You create your own light. Once you’ve found the right settings, switching to manual mode means you don’t have to worry about variations in framing that alter the average tone of the image, and thus the response of the automation. You can concentrate on your model.

If you’re new to photography, you won’t understand these explanations. It’s normal and it won’t prevent you from taking beautiful pictures!

Another criterion for using the manual mode is that newer cameras are able to increase their sensitivity without damage, which opens up new possibilities for you.

If your camera offers the “ISO Auto” option, combining it with manual mode allows you to work as if you were in both shutter speed priority and aperture priority mode: you can select the shutter speed and aperture to suit your needs, and the camera will adapt the sensitivity to properly expose the photo.

The manual mode is actually a semi-automatic mode which does not mean its name.

Be aware, however, that it is impossible to achieve a large depth of field and a very short exposure time at the same time once the light starts to fade: for example, in natural light indoors, you will not take better pictures in manual mode than in aperture-priority mode.

The space of freedom offered by the manual mode has the same limits as those to be taken into account by the semi-automatic modes.

Why is the exposure triangle so difficult to understand?

Partly because it inherits a technical vocabulary full of contradictions in the eyes of those who don’t want to dive in (and we understand them!) in the laws of optics and other mathematical arcana.

First contradiction, the trigger speed is not a speed.

This is actually a time, the time during which the shutter lets light into the sensor. The scale is not very nice since it is graduated in fractions of a second:

exposure triangle: the exposure time scale

Let’s use an analogy to dissect it: the more you are on the bottle, the less the glasses will be filled.

Similarly, the greater the number that characterizes the speed, the less light the sensor receives. Forget the “1/” before the number. At position 1000, the sensor receives 10 times less light than at position 100. We could simply write down each setting from 1 to 7 and say :

- go from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) always brings in twice as much light from the initial position. Changing from 1/2000 sec to 1/1000 sec therefore has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from 1/100 sec to 1/50 sec, even if these numbers are very different in absolute terms. It is not the initial light value (its passage time is 20 times less per 1/2000 sec than per 1/100 sec) but the fact that it is doubled.

- go from one notch to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) increases the risk of blurring if the subject is mobile. Your camera allows you to go far beyond 7 (1/30 sec), but it is your own shaking that can cause the picture to be blurred. Below 1/30 sec, you need to think about the tripod, which is outside the scope of a beginner’s experiment.

Let’s continue with the opening (or the diaphragm, it’s the same thing.).

It characterizes the size of the door through which the light reaches the sensor. The graduations of its scale are even darker than those used for speed :

exposure triangle: the scale of openings

The interpretation is the same. Forget the “f/” which is useless to you: the smaller the number that characterizes the diaphragm, the more light the sensor receives. The positions can again be ordered from 1 to 7, so that :

- when you move from one step to the next (in the direction of the arrow) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. This is exactly what we’ve already seen for speed. Thus, changing from f/22 to f/16 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from f/5.6 to f/4, even though the initial light quantity at f/5.6 is 4 times greater than at f/22.

- when you move from one step to the next (always in the direction of the arrow) you increase the blur around the subject: the depth of field decreases.

From the study of velocity scales and diaphragms two simple rules follow:

- the smaller the number (without worrying about the “/” sign.) and the more light you bring in,

- The smaller the number, the greater the blur, whether it is motion for speed or depth of field with the diaphragm.

Now we have to talk about the third thief in the exhibition triangle, sensitivity.

When the lighting is lacking, when the door is opened as wide as the lens allows, when the speed reaches the limit below which the photo will be blurred, in short when it is impossible to physically send more light to the sensor, the electronics come to the rescue of the photographer: they allow the light to be artificially amplified before the image is recorded.

Simply increase the ISO sensitivity. But here again, the scale is not graduated in a very natural way:

exposure triangle: the sensitivity scale

The numbers are increasing very rapidly and it’s anxiety-provoking. You’ve been told so many times that if you increase the sensitivity too much, the image will turn into a mush of pixels … (digital noise).

Times have changed: while it is true that it is useless to turn on the amplifier when there is enough light, all recent devices allow you to go up without damage to at least ISO 800 if necessary. It is always more damaging to have to brighten a photo with post-processing software than to increase the sensitivity as soon as the picture is taken in order to expose it correctly.

The scale can again be scaled from 1 to 7 so that :

- when you jump from one notch to the next (in the direction of the arrow) it’s all happening as if (thanks to the amplifier) you always let in twice as much light from the initial position. So changing from ISO 100 to ISO 200 has the same impact on the initial light quantity as changing from ISO 1600 to ISO 3200. You know the drill!

Just to add to the confusion, we have so far positioned ourselves on the side of the sensor.

For the picture to be properly exposed, it must always receive the same amount of light, whether your subject is in a tunnel or in direct sunlight. It’s a bit like when you salt your soup: whether the salt shaker has a small hole or a large hole, it will always need the same amount of salt to make the soup taste good. If there is plenty of salt, you will let it run for less time.

An example will give you a good understanding of the principle.

You take a picture in manual mode and it’s overexposed. So the sensor received too much light. Simply increase the value of the iris or the shutter speed to correct the problem, so increase the number that characterizes either of these two parameters.

Are you still here? So you really want to get your hands on the exhibition triangle!

You will have noticed that regardless of the selected scale, it is possible to scale from 1 to 7 if you reduce the possibilities of the instrument to its most usual range of use. The number 7 indicates the position at which the sensor receives maximum light.

These notches are perfectly equivalent, whether on the scale of diaphragms, speed or sensitivity. Each time you move from one position to the next, in the direction of the arrow, the light reaching the sensor is doubled. As a result, moving from step 5 to step 6 on the f-stop scale (f/5.6 to f/4) brightens the image in the same way as moving from step 3 to step 4 on the shutter speed scale (1/500 s to 1/250 s) or from step 1 to step 2 on the sensitivity scale (ISO 100 to 200). Convenient, isn’t it?

It is this last notion of equivalence between the different settings that must be kept in mind:

Since each notch represents the same light variation regardless of the scale selected, any action on one scale can be compensated for by the reverse action on either of the other two remaining scales.

Let’s take an example I want to gain depth of field by closing the aperture at f/11, but my picture is correctly exposed at 1/100 s for f/4 at ISO 100.

In aperture-priority mode, the other two settings would adjust immediately. In manual mode, it’s up to me to adjust them. Here’s how to do it:

exposure triangle: how to vary aperture, exposure time and sensitivity

- the diaphragm moves from position 6 (f/4) to position 3 (f/11). I therefore lose three notches from the initial exposure. To keep my picture not too dark, I have to get them back on the other two scales. I give priority to the speed scale.

- the 1/125th of a second is position 5. I’d have to go to position 8 to get the 3 lost notches back. This position is not represented on the graph, but it exists on my camera. It’s 1/15 sec. At this speed, the picture might be blurred. I prefer to stay at 1/30 sec. So I only regained two notches.

- I’m going to find the notch I still lack on the sensitivity scale by going from ISO 100 to 200.

I didn’t have to think about it. All I had to do was count the number of graduations moved on each scale, paying attention to the direction in which I was making these variations. Don’t worry, it’s much easier to do with the box in hand than to read these explanations!

Start with the two scales of speed and diaphragm. They vary in the same direction, so if you increase the number on one scale, you must decrease it on the other scale.

If you are forced to exceed position 7 on either of these two scales, report the missing increase on the sensitivity scale. The reverse is obviously true if you reach the stop on the 1 of the diaphragm or speed scale. In this case, the sensitivity must be decreased.

I’m sure you want to try! On your device, the variations may be half or a third of a notch. It doesn’t matter, the rule is always the same: the three variations combined must have a sum:

- zero if you want to get the same exposure as with the automatic,

- positive if you want to brighten the picture,

- negative if not.

A gauge on the back of your case or in the viewfinder allows you to see how your adjustment is positioned in relation to the central position, the one that the automatic system would have chosen. Be careful, it moves only if you are in manual mode!

exposure triangle: the display of the exposure in the viewfinder of a Nikon reflex camera

To conclude, try this little test that will allow you to know if this tutorial has achieved its goal: to de-dramatize the exhibition triangle!

Question 1: Which of these three settings is not equivalent to the other two?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/60 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/8 | 1/30 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

Question 2: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to photograph a landscape at wide angle?

| A | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

| B | f/11 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

| C | f/11 | 1/100 s | 200 ISO |

Question 3: Which of these 3 settings would you choose to make a portrait that stands out well indoors against a blurred background?

| A | f/4 | 1/15 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/4 | 1/30 s | 200 ISO |

| C | f/4 | 1/100 s | 800 ISO |

Question 4: Setting A gives me a picture that is too bright. Which of the 2 others should I choose to darken it?

| A | f/8 | 1/250 s | 200 ISO |

| B | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 100 |

| C | f/5,6 | 1/1000 s | ISO 400 |

Question 5: Which of these three settings is the best?

| A | f/2,8 | 1/500 s | ISO 100 |

| B | f/11 | 1/1000 s | ISO 3200 |

| C | f/8 | 1/250 s | ISO 400 |

Question 1

A and B are equivalent (-1 on the diaphragm and +1 on the velocity). C is +1 on the diaphragm, +1 on the speed but only -1 on the sensitivity. With setting C, the picture will be clearer.

Question 2

The 3 settings are equivalent in terms of light. To have a large depth of field, you must close the iris. The answer would then be B or C. But why increase the sensitivity when 1/100 s allows you to take a sharp picture? So the best answer is C.

Question 3

The open f/4 f-stop gives a blurred background with the 3 settings which are otherwise equivalent in terms of light.

At setting A, the subject may be blurred because the shutter speed is too low.

Answer B would be suitable for a still subject, but when you’re doing a portrait, you’re close to your model (between 2 and 3 meters) which amplifies the movements. If possible, it is better to increase the speed to avoid blurred movement.

The answer C is therefore the best. 800 ISO is not the end of the world!

Question 4

Settings A and C send the same amount of light to the sensor. The correct answer is B. This setting is two notches below the other two.

Question 5

Don’t tell me you’ve answered that nonsensical question? There is no such thing as a “right setting” in absolute terms. You always have to consider the situation.

The A setting leads to a very small depth of field, especially if you are close to your subject, but perhaps you are looking for a smooth bokeh?

Response B uses a very high sensitivity. It is suitable for a fast-moving subject for which you need a large depth of field.

The answer C is well balanced, but the speed will be insufficient if your subject is moving fast, and the depth of field will be too great if you expect a blurred background.

In short, there is no good answer to this question!

If you got 5 correct answers, you have mastered the exposure triangle perfectly.

Between 3 and 4 correct answers, you’re a little distracted. Any inattention error will result in a poorly exposed photo.

If you have between 1 and 2 correct answers, the author of this article has missed something!

Use the comment box below to ask questions that will help us make this tutorial clearer. In the meantime, you have plenty of fun with the semi-automatic modes!

Learn more about Jacques Croizer’s photo guide …

Discussion about this post